By Juliette Grossmann

This article is the second of a series that draws the first intermediary conclusions from the “Creative Collective Practices for Transformation” project, as part of the Plurality University Network’s Narratopias program: “Collective creative practices for transformation: first lessons learned.”

A Google doc version is available for download, and to receive your comments.

The political project of Collective Creative Practices

Ever since the beginning of the “Collective Creative Practices for Transformation” project, its name has been debated. If “naming the thing is enough for its meaning to appear beneath the sign”, as writer and politician Léopold Sédar Senghor wrote, then our task is a difficult one: agreeing on a name that embodies the meaning of this experimental and collective research project. Each of these words: practice, collective, creative, transformation, was chosen carefully. Yet they all deserve to be explained, both for us to frame our work and set the limits of the projects we chose to include or not, and for others to recognise themselves and feel integrated in the project. This is not about branding, but rather about identifying the subject of our interest and focusing our efforts in the right places. Several recurring questions arose among the Plurality University team: how shall we describe our project? What words shall we use? What practices and groups shall we include or not? We realised that defining words always brought us back to an underlying question we could not answer: what does acting for transformation mean? Is it not just another word to say we are acting at the political level, by wanting to change the way people live together in our societies? It then occurred to us that defining this political project would both clarify the meaning of the Collective Creative Practices project and set a common ground for the practices we gather.

This article tries to answer these questions, first by linking the issue of wording with the political issue. Secondly, by distinguishing what is ethical from what is political in these practices (through a reflection on the practices we carry out at U+). Thirdly, by defining the political dimension of the collective creative practices we observe through their capacity to recognise differences and take them into account: an eminently democratic perspective. And lastly, by questioning these practices’ objectives and their capacity to generate collective norms or actions based on common concerns with the world.

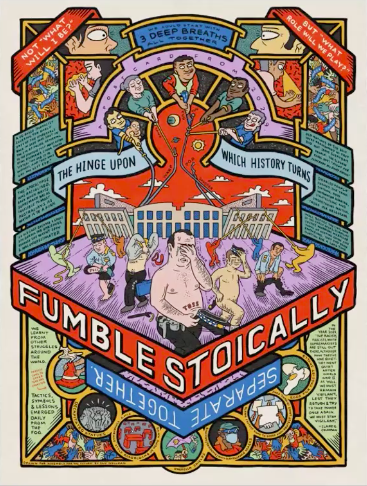

A Postcard from 2029: Dispatch by Sam Wallman from the First Assembly for the Future, from The Things We Did Next (see Agora 5).

Finding the words

We are at a point in Western history where political positions are very clear-cut and centred around fundamental issues people cannot seem to agree on: ecology, feminism, immigration, capitalism… Gaps in existing opinions around these issues are widening. This reality materialises in the words we use, which can be associated with different opinion groups. For example, though both statements are technically true, saying that we, at U+ “create an alternative collective approach towards transformation”, or that “we develop an innovative futurist project” implies completely different - and even politically opposed - associations of ideas. And that is the problem: this choice is not technical, it is political. Either of these expressions will allow some people to identify with us and take an interest in what we do, and others will dismiss us as people they do not care about or are opposed to. Choosing the right words is most certainly not a new problem, but it is even riskier in the current context of political tensions, radicalisation of speech, and strengthening of information bubbles on the Internet (1). U+’s team discusses what words to choose to describe our actions on a daily basis. Though giving an account of the plurality of our points of view is difficult, there comes a point when we must say something collectively.

This task is all the more complicated since we wish to open the Collective Creative Practices project to as many different people as possible and make sure that people and organisations with different opinions meet in debating spaces that are open to all. Because of this requirement, we avoid saying explicitly where we stand politically as well as connecting our activities to specific political movements. Though Collective Creative Practices does not place itself in the field of politics, it is an eminently political project. Not only do we convey political values and ideas through this project, but the search for a political transformation is one of the necessary criteria of the practices we involve in the project. Then how can we balance non-exclusion with the political project? And how can we clarify our political expectations towards practices? To create a field of practice, we must first and foremost reflect on how we characterise the political dimension of the Collective Creative Practices project, and by extension the political dimension of the practices that constitute it.

Setting boundaries: between ethics and politics

We noticed a common thread between most collective practices we came across: they pay great attention to the way people talk to each other, and to the diversity of participants. For example, Alex Kelly and David Pledger from The Things We Did Next describe the different actions they have implemented to bring in diverse audiences: a partnership with a university to attract students, another one with a secondary school, specific communications towards Australian First Nations peoples to encourage their participation… Inclusivity also works the other way around, by excluding people whose behaviours do not respect the values promoted by the collective.

As an association creating projects and collective practices, we at U+ had to explicitly define these different values, and we were pushed to do so by members of our Board who were personally affected by discrimination. Ethical values give a direction to several aspects of any given practice, towards what we consider to be fair and right, which is defined individually at first and then collectively after discussing the subject. These values include the practice’s ways and means, the behaviours and ways of doing things together, the people involved or not… These discussions resulted in the drafting of a code of conduct for the Plurality University Network. For example, sexist behaviours are forbidden. But the rule is not enough, as it can be applied and interpreted differently according to the context. We value the fact that the Plurality University is a space where men and women are free to express themselves according to the same rules: a man “hogging” the conversation would be considered to have an undesirable behaviour. Yet we cannot make a rule out of this, except by asking everyone to respect a given time limit to speak, which does not seem desirable to us either. It is therefore left to the discretion of each individual to explicitly condemn this kind of behaviour when necessary, without making it a binding behavioural norm.

This observation led us, as a team, to reflect on the following question: do we have red lines when it comes to including a collective practice in our project? Things we consider to be unacceptable in a collective practice? We easily agreed that hate speech (racism, xenophobia, anti-Semitism, sexism, anti-LGBT) would be unacceptable to us (whether conveyed by the collective or tolerated when it comes from one participant in its workshops). Things get tricky regarding more divisive subjects: climate scepticism is a red flag for some people, for others it is acceptable as long as it is backed with arguments. It appears that we have a few non-negotiable and definite red lines, but most of them are rather limits. They mark the line between what we agree on, and what should be discussed. Such a dialogue helps highlight the values that underlie each person’s choices and behaviours. The objective is not to agree on a single right conduct, but rather to open the discussion on the questions that need to be asked in specific situations, and to define an ethical common ground on which we could all agree.

This common ground could be found in the respect of values that are intrinsic to ethics, as defined by philosopher Emmanuel Levinas, who defends the idea of “infinite responsibility” for the Other’s vulnerability (2). The meaning we give to our practice is then defined by the value of the encounter with the Other, which allows us to recognise his/her fragility, and be responsible for him/her. Though this may sound abstract, it appears that the principle of individual responsibility towards others is what drives us at U+ to act with caution during our workshops, to take care of each individual, and to include marginalised or underrepresented people so they can show their faces (within the meaning of Levinas’ definition, i.e. creating face-to-face transformative encounters). Most collective practices we have encountered have integrated some form of this morals of individual responsibility, of care for the Other, and recognise everyone as conscious and unique subjects.

Though ethics help delimit several aspects of a collective practice - both through discussion and the personal and collective questioning of the people involved, and through the recognition of a responsibility towards the people met during these practices - it appears, however, that it is not enough to characterise a practice’s political project, which seems to lie elsewhere than in values.

The political project: plurality and inequalities

The Collective Creative Practices project seeks to bring together creative and collective initiatives that work towards an ecological and social transformation of the world. This goal is clearly political though it lacks a clear definition, both by us through the selection criteria of the practices we invite, or by the collectives undertaking these practices. Still, we noticed that the practices that best define the way they articulate their intentions, goals, and methods, and that clearly state where they stand in specific political contexts, also happen to be the most relevant ones.

For example, SPACE’s Rehearsing the Revolution method - which was introduced by Petra Ardai during the first Agora - was created to enable politically divided audiences to find common ground through the co-creation of a shared story. These methods have been tested in specific political contexts, notably in the areas of Cyprus that are disputed between Greece and Turkey, or with Roma communities in Hungary. The strength of this method lies in its ability to bring conflicts to light, to recognise diverse truths, to take account of the differences between the people involved, and to allow them to rediscover forms of dialogue using imagination and fiction. Rehearsing the Revolution’s website reads as follows: “The project allows the audience, who are active participants and not passive spectators, to experience what it is like to look at the same reality differently, where the differences lie and, above all, where the common ground can be found”. And this is purely political.

In his article What political speech means, political scientist Thibaut Rioufreyt maps different meanings of the concepts of politicisation and depoliticisation of a discourse. He explains that “what is considered to be political can be seen as a form of expression and a way to deal with differences”. He then goes on to say: “At the root of conflictualisation lies the recognition that societies are not only pluralistic, but also unequal. Politicisation is thus inseparable from the identification of a form of social relation marked by domination mechanisms”. The political character of a project such as Rehearsing the Revolution then becomes obvious: the collective imagination work is integrated into a plural vision of society, impacted by dominant and unequal relationships that are recognised and addressed throughout the methodological process.

Consequently, politicising a practice does not necessarily mean getting involved in politics with politicians nor having a defined and common idea of what ecological and social transformation should look like. Instead, it means anchoring one’s practice in a political vision of society, one that considers the power, inequality and plurality issues at stake, as those are specific to the world in which the practice takes place. For example, Finn Strivens, who described his Tomorrowland project in an interview we conducted, works with the charity Sirlute in order to run his workshops with young, struggling people in the outskirts of London. As a result, social inequalities are explicitly addressed during his workshops.

Conversely, Thibaut Rioufreyt explains that some discourses also “create depoliticisation through non-reference, euphemisation or denial of difference”. The difficult part is to differentiate a discourse that seeks neutrality through uncertainty and non-reference, from one that takes differences and conflicts into account, while accepting uncertainty because of its experimental character. In other words: does uncertainty about a practice’s political project (i.e., the transformation it seeks to bring about) show depoliticisation, or rather the open character that comes with any experimental practice? As Lara Houston of the Creatures project pointed out during the second Agora, we must “take care” of the experiments and let them unfold before criticizing them for their instability and their trials and errors. Of course, building and perfecting a political discourse as the practice progresses is important, but it must not imply having to water down or erase the political disparities that inevitably exist in any collective work on the future. The future is a space for political struggle.

The political project: public spirit and collective norms

Besides the recognition of differences, another dimension of politicisation is what Thibaut Rioufreyt calls generalisation, i.e. a discourse that is “oriented towards the public spirit” (3), as sociologist Nina Eliasoph defines it. This kind of political discourse - a sine qua non condition of democracies - must be “open to debate and addressing issues affecting the common good, the good of all”, explains Rioufreyt. As opposed to individualisation, political discourse is characterised by the fact that it invokes norms, values and principles at the polis or community level and not at the individual level or for specific situations. In that sense, being part of the ecological and social transformation of the world and reflecting on the collective future of our societies and of our coexistence are true political acts. As philosopher Hannah Arendt wrote: “The moment I act politically I am not concerned with myself, but with the world”. This collective concern for the world is one of the things that brings together the collective and creative practices we work with.

Thibaut Rioufreyt specifies the generalisation at work in political practice: it is “both normative and performative, and it refers to the statement of what must collectively be, and to the creation of a collective solely by announcing it and speaking in its name”. These two forms of generalisation can be found in most practices we have encountered, although sometimes one is more present than the other. The performative dimension is crucial to some practices insofar as they seek to constitute collectives through their practice, and thus build communities of thought on issues of transformation. For example, the Untitled project intends to create collective actions: “any part of a real transformation requires some types of alliances and coordination among actors, and we want to be the infrastructure and space for that”, Johannes Nuttinen shared with us during an interview. For that matter, most practices have emerged from a meeting between people with shared interests, who then formed a collective around a project, an idea or an intuition. During the second Agora, Kelli Rose Pearson of the Re·Imaginary project explained that it was born out of an intuition shared by first two, then several researchers and practitioners: “We are a collective of practitioners and researchers exploring how creative methods can support deep change towards just and ecological cultures”, their website states.

The normative dimension of collective and creative practices’ political discourses is not as clear: what norms for societies are defended by these practices? Some collectives do not define these norms. For example, the methodology Ketty Steward had us try out during the fourth Agora did not aim to formulate common standards nor to start a debate. The goal was totally focused on creating a collective around the common creation of a story. The collective arises out of cocreation rather than through a normative political discourse. The transformation Ketty seeks is the empowerment of the individual through the experience of collective imagination. This is also the case of projects such as the Science Fiction Committee, or Urban Heat Island by Juli Sikorska. However, although they are not always explicit, these practices indeed convey norms: most of them advocate for horizontal and collaborative forms of governance and more equal inter-species relationships, to name a few. These norms are very diverse, and they are not always formally expressed, which makes articulating practices all the more complicated. However, the uncertainty of norms seems to be what makes these practices accessible to a wide audience that comes together for the experience and ends up finding more or less common norms in the process. Most collective creative practices formulate very little norms to allow for freedom, diversity and open-mindedness. This is also where the artistic and experimental dimension comes into play: creative freedom can easily do without norms - “but not without constraints!”, as Ketty Steward likes to recall. She uses literary constraints to help us use our imagination without feeling paralysed by the immensity of possibilities. This virtual absence of political norms (which often goes hand in hand with the flexibility of methodological norms) allows practices to evolve as experiences take place rather than remaining fixed in one initial discourse.

To politicise or to depoliticise, that is the question

The issue of politicisation (of companies, universities…) and depoliticisation (of State, citizens…) is currently very acute, and it is no coincidence that addressing the definition of collective practices’ political project is so complex. Some collectives advocate for politicisation as a necessary recognition of power relationships (how can any collective issue be addressed without including inequalities and domination?), others seek to free themselves of politics and to focus instead on the human experience and individuals (conversations between human beings might succeed where politics failed). However, the proliferation of actors practicing and talking about the future and imagination means we have to clarify what we are trying to do in the Collective Creative Practices for Transformation project. By carefully listening to the discourses of the different collective and creative practices, we can try and formulate the conditions that unite us: exemplifying an ethics of responsibility and care, defending the importance of democratic dialogue within collectives, taking existing power relationships into account, highlighting the diversity of opinions, and the prevalence of topics about the common good. A tension remains regarding norms: how can we be as open-minded and creative as possible without depoliticising a practice? And how can we formulate political norms without ending up bringing together only like-minded people?

Besides what collective creative practices say, what do they do? We cannot experiment with all methodologies, but the interviews we conduct help us clarify practices (provided collectives are transparent about their goals, interests, and processes). Agoras are also enlightening moments where the collective experience of practices clarify the relationship between discourse and action. They are nevertheless limited by their virtual and punctual nature, while the physical and repeated experience is often part of the process of collective creative practices. We are still reflecting on the complex link between the collective aspect and the transformative power of these practices.

<Chloé Luchs-Tassé further explores this issue in the third article in this series, “Sailing the archipelagos of collective practices”. >

Notes :

- Eli Pariser, The Filter Bubble: What The Internet is Hiding from You, 2011.

- Emmanuel Levinas, Totalité et Infini, La Haye, 1961.

- Nina Eliasoph, Avoiding politics. How Americans produce apathy in everyday life, Cambridge University Press, 1998, 352p. Link to book

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.