Jen is an award winning artist-researcher of Canadian Métis-Scottish descent, living and creating on Wurrundjeri and Dja Dja Wurrung Country. Her practice-led research is centred around cultural responses to climate emergency, specifically the role of artists. Her work is engaged in discourses around food justice, disaster preparedness and speculative futures, predominantly articulated through transdisciplinary collaborative methodologies and community alliances. Jen creates and contributes to experimental multi-platform collaborative projects, including being a core artist of Arts House’s REFUGE project, and co-founder of the Centre for Reworlding.

Project Information: Centre for Reworlding

The Centre for Reworlding prepares future generations to mitigate against the impacts from the deepening climate crisis. Grounded in First Nations* knowledge systems and protocols, the Centre for Reworlding focuses on working towards intergenerational justice, building creative resilience and applying intersectional collaborative approaches in how we work with others— so we can adapt climate disaster risk reduction and resilience strategies to meet the needs of diverse communities. The Centre for Reworlding amplifies arts and culture’s leadership capacity in climate emergency, disaster risk-reduction and resilience contexts via: the development and presentation of multi-platform art projects; innovative labs and workshops; cross-sectoral partnerships and collaborations; and research and advocacy.

How did the Centre for Reworlding start?

At the occasion of an Assembly for the Future - a collective futuring practice created by Alex Kelly and David Pledger from The Things We Did Next - I wrote a speculative narrative based on the idea of a Centre for Reworlding in Australia. I was already collaborating at the time with Claire G. Coleman, with whom we made a film of a speculative indigenous future called Refugium. Looking at the idea of a Centre for Reworlding, we asked ourselves: what would it take to actually make it, and who could we build it with?

We obtained some funding, particularly from the Australia Council of the Arts. Now we are in our second year, we are starting to build programs, creative projects and collaborations. We are 10 ‘Reworlders’: Indigenous, people of colour, settlers and LGBTIQA2S+ artists, scientists, thinkers and change-makers, based on the unceded lands* of the Dja Dja Wurrung people in Castlemaine, Victoria, Australia. Claire and I lead creative development, Angharad Wynne-Jones leads our strategic initiatives, we have a social scientist, an expert in resilience… We bring these different levels of expertise together, also with local and context specific experts. Our work is highly collaborative!

In what ways do you work with artists?

We collaborate with artists by amplifying their practice, and its impact. For quite some time, a lot of what I was doing was trying to advocate for artists to be a part of the conversation in the climate space or in disaster management. Working in a resilience space requires a certain skill set, certain literacies. For transdisciplinary collaboration to work, it’s about making new knowledge together, and being able to speak each other’s languages. You don’t need to know the whole discipline, but you have to be able to understand.

In the climate space, there has been a real deficit of First Nations voices, people of colour, the LGBTIQ+, the disability sector and so forth. These are often knowledge and skills outside of traditionally hierarchical ratified sources.

In Australia, we are slow at looking at culture in the climate context. Lots of groups exist, but there are no bridges between them and no links with the decision making. Usually, the art and cultural sector is instrumentalised, or decision makers just don’t see how it is their business.

Through an art project called Refuge at Arts House, we’ve been rehearsing climate-related disasters, like a heat wave, a pandemic, a flood, climate-related displacement, and really working with communities, with emergency services, local governments, and Indigenous knowledge keepers. We’ve been practicing and rehearsing disasters through Refuge for 7 years. Several of the ‘Reworlders’ at the Centre for Reworlding have collaborated in Refuge and we pay homage to the creative methodology developed through Refuge in some of our programs.

Could you tell me more about the work of the Centre for Reworlding?

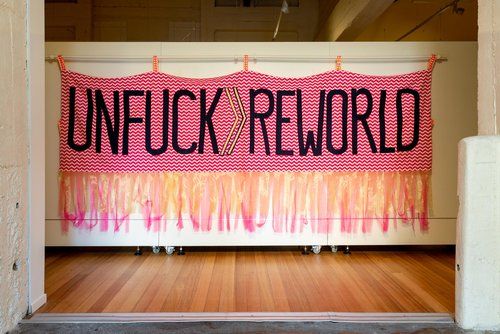

We have three main programs. First, we do something called Protest Methods and Banner Making Workshops. We work with youth and young people to enable a knowledge transfer from people who have been activists or have done social transformation. The young people make the banners and put them into a banner library. A lot of labour gets wasted in the making of banners every protest, so it’s a way to bring young people together, to start forging relationships and build literacy.

We also have an Artist Climate Lab, where we bring artists into the room to bolster their literacy about the climate context and potential impacts. We look at how you can stretch time, how you can reorient your practice as an artist. You don’t have to be making work specifically about the climate. You might already be working in one little area that you could amplify, or looking at ways in which you can collaborate with others on climate-related matters.

Once we start building the capacity within these two groups, then we lead it to the Creative Resilience lab. That’s when we gather all of the people in the disaster management space (philanthropists, decision makers, etc.) along with the artists and the young people. It’s a two-day lab enabling knowledge sharing and cross-sectoral collaboration with communities. We use scenario planning, speculative exercises, movement exercises, timeline exercises… All these different methods aim to foster hyper-localised relationships. Understanding the local context of what might eventuate in the community and seeing where the expertise is so when that event happens, there’s already a strong social fabric.

Daniel Aldrich, who is an expert on disasters and social transformation, talks about the importance of ‘bonding, bridging and linking social capital’. People in bonded clusters might be unified because of cultural reasons or work, relationships or family relations. In order to bridge these clusters together to develop a broader baseline, you need to organise certain activities. And then you must link them to the decision makers. So, what we try to do is unify some of those groups through this bridging activity, with the decision makers in the room.

Expertise can come from all different places; it’s all based on relationships: who you know and the experiences that you had. That’s really what we’re doing in the Centre for Reworlding as well as doing creative projects that create platforms for other collaborations or other ways of bringing a First Nations approach to understanding the climate emergency.

What are you trying to transform through these programs?

One thing that we really work on is helping people realise that they bring their complex identities into any of the work that they do. During a crisis, they might have a specific role with a uniform and a job description, but in the event of a disaster, they’re actually bringing all of who they are. Especially in regional towns like where I live, the people who respond to a disaster are often the people who are impacted by the disaster, and this reality will largely impact the ways in which the community will react to the event. If you are queer, you’re bringing your queer perspectives; if you’re a single mom, you’re bringing that perspective.

I was invited to do a keynote for an event around the creation of a national disaster framework for Australia. I fell off my chair when they invited me! The experience provided me access to leading disaster management material which enabled me to better understand their language and methods. There was a whole part on the values: what we value before disaster, what we value in the event of a disaster and what happens after a disaster. In the event of a disaster, people usually come together in the name of solidarity. But after it dissipates, lots of people go back to their business as usual, which we’ve seen throughout the pandemic. Unfortunately, not everybody bounces back. What we work on in the Centre for Reworlding is: how do we bring these values into the future? Such as collectivity, intangible rewards, environment-first over economics, etc.

Why is it necessary to include the future in this thinking shift? How do you think that speculation can help?

When we’re dealing with thoughts of apocalypse or the end of life, we fall back into those reptilian thoughts of fight, flight, freeze. When we engage with the discipline of the imagination, we start to think outside of the here and now. We’re able to move from nihilistic or fundamentalist thinking to something that you can actually take action for.

We live in an area that has really high bushfire risk. I would say that just a small population has emergency kits. One of the projects I did outside of the Centre for Reworlding was called Ready, Steady, Go!. It was about thinking beyond the nuts and bolts of what goes into emergency kits and making them more specific to the context of what sort of disasters might affect you and what the specific needs you, your family and your community may need in an emergency: for comfort, care, healing, cultural needs… We ask: what would you take if you had to leave your house, but also, what if you had to stay and wait, or be at home for two weeks without electricity, etc. With the what if scenarios, we’re engaged in the imagination and speculative practice. We can’t engage in the imagination as much when we’re in survival mode. This shift helps people understand that preparedness thinking is an adaptive way to be responsive rather than reactive in the event of a disaster and hopefully achieve better outcomes.

We’re living in this period of ‘unness’, everything about the future right now is unpredictable, unimaginable, uncertain… But if we want to reworld, we must think about resilience, resurgence, reconciliation, about things that form relationships. And then through that, we start to be able to sit with the uncertainty. As an artist, that’s something that we do, it’s fodder to the things that we create.

Many people criticise the concept of resilience used in public policy, as a denial of the real trauma of a disaster (especially for the socially disadvantaged groups) and being more about persistence of systems than change. You work explicitly on resilience, what do you think?

I completely agree with you! We called our project the Creative Resilience Lab but we actually have issues with both words, ‘creative’ and ‘resilience’. But these words allow us to be part of the conversation. Did you know that ‘creative’ is the number one word on LinkedIn? Usually, it is a major value that employers ask of their employers, but the second they’re hired, they’re not asked to be creative but to be implementers. The word ‘resilience’ is used by decision makers because it is rooted in power: they can say it because they hold the power. Even the word ‘vulnerable’ is highly problematic. So we use them in a way in which we can question them with the people directly involved in resilience policies. Usually, I prefer talking about Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s concept of antifragility, that is about the transformational aspects of resilience. One impulse after a disaster is to point blame, whereas we work on what we must learn to do better next time, how we can transform the system.

Incinerator Gallery, June 22, 2015

When working on risk management in a previous research project, I observed that departments and individuals tend to think and act in closed, straight lines, each in their own speciality, one emergency at a time, which becomes a problem when dealing with large-scale, multilayered crises.

We encountered this all the time in the Refuge project with our different stakeholders. They want to know what the outcome is, we observed this distilling process of constantly trying to get into a funnel so that they can action something. Whereas what we do is flip the funnel upside down, and just keep opening up and opening up, and trust the artists to make the connections. This helps us find threads or issues that might get overlooked, ignored or hidden. We know as artists that creativity is a process that takes time. It can’t be rushed. Otherwise, we risk doing something that’s been done before, is boring or under-researched.

We ask: who are the voices that aren’t represented in the room? What are the things that people keep saying over and over again? There’s a term that I love in Australia: ‘the too hard bucket’. It means: it’s too hard so I’m just gonna put it in a bucket over there. As artists, because we’re in the imaginary space, we take the too hard bucket and say let’s pull it all out. When our stakeholders are worried about money and resources, or wasting time, we can do that as artists, we can go into that space.

When working with the city of Melbourne in one of our labs, we asked them: what happens if you have an apartment fire, a flood and a windstorm. The team said: we can only deal with one disaster at a time. So that is exactly what we rehearsed with them - this is actually likely to happen in the future. Over the years, all of the emergency services that have worked with us have embraced what we do because they can’t work in the speculative space as part of their job. They’re in positions of authority and that’s what the public sees from them and asks of them. But in the speculative space we will ask them: what’s the one thing that you can’t do in your job that we could do through a speculative exercise?

Do you have ways of evaluating your practice?

For example, the city of Melbourne approached myself and two other artists, asking us to co-design and co-facilitate their annual emergency drill, part of their municipal emergency plan. They bring together a broad range of stakeholders such as the police and ambulance services, public transportation and health services to explore, test and plan their communications and processes in the likelihood of a specific disaster scenario. Emergency services often spend a lot of human and material resources trying to engage communities in preparedness planning, but often don’t achieve the same participation or attendance. But this time everyone came and stayed because they were getting something out of it. But in their internal evaluation process, they didn’t take this into consideration, as an important value. Even though, when doing knowledge transfer, people will remember it a lot more if it’s fun and relational. This is something my colleague Jonathan mentioned in an interview for the Creative Recovery Network’s podcast Creative Responders. And, I’m currently writing an article on the role of artists in this exercise.

When we started the Centre for Reworlding, Claire Coleman and I worked with Indigenous elders on protocols that are really important to the way we work, the way people are present in the room, their expectations, how we mitigate if something goes awry in the process… And we continuously learn from them. Essentially, they are about asking people to cross the threshold into that speculative space, where they’re going to feel uncomfortable. But hopefully, by the end of the process, they feel comfortable being uncomfortable and dealing with the complexities because it’s in the imaginational space.

Image from the film Refugium

Have you formalised and shared some of these protocols, or other tools and methods?

Claire and I just published an article in a book called Failurists: When Things Go Awry, looking at Reworlding and creative failure. Later this year, we will be publishing some of our protocols. Everything that we write is Creative Commons. On the other hand, from a First Nations perspective, taking pictures of the protocols during a workshop for example, can be seen as very extractive. The way we embrace knowledge is not about the content and the information, but the relationship in which the knowledge is generated, the quality of the space between the speaker and the listener. So we are sharing the protocols because the elders have allowed us to do it, but when we introduce them, we contextualise them. When people just take the protocols and implement it, there is no relational accountability, which hurts us all. In oral cultures, Indigenous knowledge and practice are based on this relational accountability of being able to tell the story and keeping it going. Colonisation is all about severing those storylines and focusing on the individual instead of the collective. So we do share, but we also contextualise that in receiving this, you’re actually holding these relationships, which is very important in the climate context. If you use our methods, let us know, maybe we can amplify what you’re doing, maybe we can work with you or broaden your impact.

What are you working on right now?

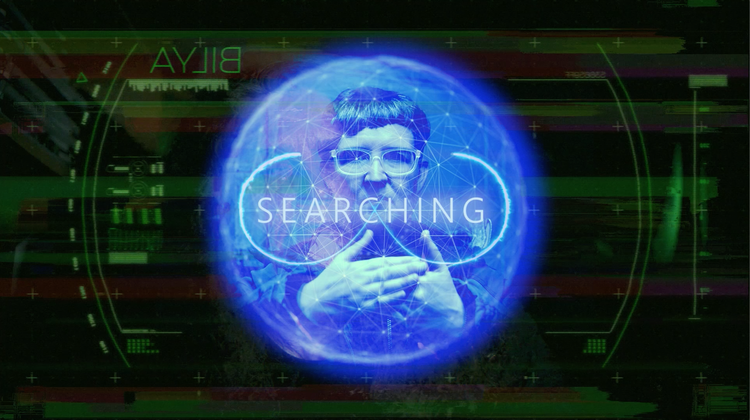

In 2021, we made a film called Refugium. 6,000 years ago, when climate change impacted Australia, there were massive floods. A lot of the tribal groups moved inland and ended up having to come together. So they had to reorganise and develop a new system of governance. We wrote this film based on that story, but also linking it to what happens in biology around living organisms when they are in hostile environments that threaten extinction. In the film we invented a portal called Bilya. It comes from the Noongar language, it means river, ecosystem, but also belly button, which is the nerve centre. The same way we created the Centre for Reworlding, we are now looking at how we could actually build Bilya. It is a speculative creative research experiment. The idea is to create a network of networks that could be held by everyone involved. It’s kind of linking Academia.edu, LinkedIn and Facebook so that there’s different levels of value! We are looking for resources to create it. We would love to partner, collaborate or connect with anyone who could help us with this goal!

Interview conducted by Juliette Grossmann.

*Glossary

Indigenous/First Nations: Australia is made up of many different and distinct Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups, each with their own culture, language, beliefs and practices. They are the oldest continuing living cultures in the entire world (they were here for thousands of years prior to colonisation), carried on by the descendants of the first peoples.

Reconciliation is about strengthening relationships between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and non-Indigenous peoples, for the benefit of all Australians. According to Reconciliation Australia, it is based and measured on five dimensions: historical acceptance, race relations, equality and equity, institutional integrity and unity.

Reworlding is the unification of three Indigenous futuring and survivance relationships: rematriation, reconciliation and resurgence. Rematriation is an Indigenous way of life that recentres respect, restoration and care for Mother Earth and kinship relationships between each other and all life forms. Reconciliation is about repair, healing and making amends for past and present colonial injustices, and establishing equitable and respectful relationships for the future. Resurgence is about reclamation, renewal and revival – honouring our ancestral legacies, complex cosmologies and reconnecting storylines.

Rae, J., Coleman, C.G. (2023) Reworlding: Relationality in the climate adaptation emergency.

Settler colonialism is the elimination of First Nations Australians and their replacement by a settler society. Initially carried out by violent means, settler colonialism continues today in the form of cultural assimilation. Settlers are the people who benefit from this system because of their ethnicity.

Unceded land means that First Nations people never ceded or legally signed away their lands to the British Crown, making them stolen territories. Before an event or when creating a project, it is proper protocol to acknowledge the host nation, its people and its land.